by Ruth A. Symes

[After a family visit this summer to Gawthorpe Hall, home of Rachel Kay-Shuttleworth featured here, I was reminded of my article published in Who Do You Think you Are? Magazine (2013)]

Link to buy my books Amazon.co.uk: Ruth A Symes: books, biography, latest update

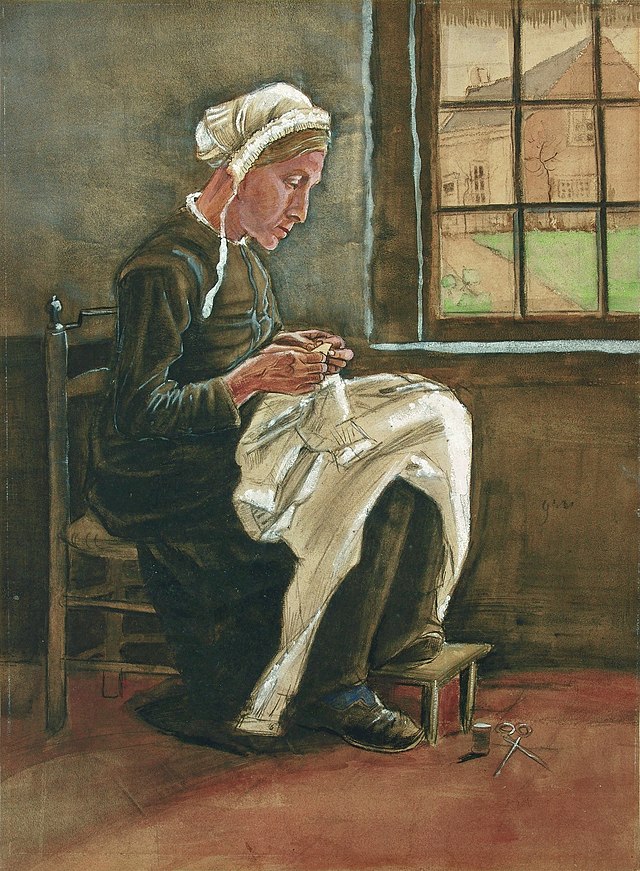

Woman Sewing By Window (1871), by Vincent Van Gogh. Via Wikimedia Commons.

The Great British Sewing Bee, the hit BBC series that set out to discover the nation’s best amateur sewer, has definitely touched a nerve. There’s no doubt about it, sewing and home crafts in general are enjoying an unforeseen resurgence in popularity. In fact, immediately following the launch of the programme, John Lewis reported a massive increase in haberdashery sales with branches noting record requests for ‘bias binding tape maker’ (featured in the programme), sewing machines and dress-making fabrics.

Rather than creating an interest in home-sewing and craftwork, the Sewing Bee, has tapped into a recent increased public interest in these skills. In the past couple of years, craft shops and college courses have reported a large rise in people wanting to learn traditional textile and craft techniques. The reasons for this are probably tied up with the recession. It’s not so much that the items produced by home dressmaking are cheaper but that the hobby overall is inexpensive and can be done at home. Craftwork both relaxes and gives a sense of achievement (even joy) – sensations that have become more highly valued in this era of stress, competition and frequent disappointment. Additionally, manufactured clothes are perceived to be of poor quality and design and indicative of third world exploitation.

And there is also, of course, a nostalgia in needlework that links us back to our ancestors. Sewing and fabric-based crafts are at the heart of the domestic history of British women and the family. Not that long ago needlework was still a firm part of the school curriculum for girls, and not long before that darning and dressmaking were integral aspects of what it meant to marry and become a mother.

Over the course of the nineteenth century, improved communications (particularly railways) meant that ideas about fashion could be disseminated more widely and more quickly, and better printing techniques, cheaper paper and improved literacy meant that there were more women’s magazines catering for the desire for stylish clothing and home furnishings. At the same time new machinery was producing more abundant and cheaper materials (especially cotton), more people were being paid their wages in cash and chose to spend it on adorning themselves and there was a huge increase in the market for cheap, fashionable clothing and other household items made from fabric.

Starting in 1860 and lasting until about 1930, there was a backlash against the faceless industrialised processes that produced many of these items. Central to this period was the Arts and Crafts Movement which promoted traditional craftsmanship with an emphasis on handmade decoration. Whether they were employed in the needlework industries or created bespoke items at home for their own use almost all our female ancestors would probably have been far more comfortable with a needle between their fingers than with a pen.

Hand stitching techniques such as ruching, chain stitch or herring-bone stitch of course go back into the mists of time, but materials, implements, techniques and even the sequence of putting pieces of material together to make clothes have changed over the centuries as styles have gone in and out of fashion. ‘Smocking,’ for example, (which was a type of surface embroidery in a honeycomb pattern across pleated fabric) was a popular technique in rural costume in the eighteenth century but by the early nineteenth century ‘smock frocks’ were disappearing and smocking of a more delicate kind using cotton floss was making an appearance in the dress of middle-class women and children. Another good example which can be pinpointed to a specific historical period is ‘Berlin work’ which was particularly popular between 1850 and 1870 when new synthetic dyes created brightly-coloured yarns that could be woven through canvas to produce attractive three-dimensional effects. Furniture covers, cushions, bags and clothing from this period all demonstrate this technique.

Clothes coloured with the new aniline dyes, mid nineteenth century, Gawthorpe Hall. Author’s own collection.

There have, of course, been some very significant developments in the history of dressmaking. In 1863, the American tailor Ebeneezer Butterick (and his wife Ellen) invented the tissue paper dress pattern (and standardised clothing size chart). Before long, such patterns were popular in Europe. Amongst other publishers, Samuel Beeton, husband of Mrs Beeton, made such patterns popular by inserting them (together with fashion plates) into his publication, The Englishwoman’s Domestic Magazine. Sewing machines were first patented in 1846 but were not in general use until the 1860s.

Family history is tied up with fabric in many different ways. Needlework skills were particularly called into service at key moments in the history of a family such as births, christenings, engagements, marriages and deaths. And it’s remarkable how many of the oral history memories of elderly relatives are strewn with references to outfits that were made, mended and worn in the family for certain occasions. In addition, we are all familiar with the business of trying to date family photographs from the cut of a suit, the length of a hemline, depth of a cleavage or shape of a sleeve (for more on this see the family history titles by Jayne Shrimpton and Robert Pols).

Surviving garments themselves can give even more clues to the lives of their past owners, hand stitched or machine sewn, details of cut, choice of material, the placement, style, material and number of buttons, subtleties of shade and style all tell us something about the maker and the wearer – their level of wealth, the degree to which they were fashionable, the society in which they lived and worked. Many garments and fabrics speak to us of the past: from the tartans which may denote to which Scottish clan your family belonged, to certain luxury materials that breathe of exotic lives spent in other parts of the globe, from the motif on a school tie or blazer that declares an ancestor’s membership of a particular public school or association, to the dozens of hooks-and-eyes on an old dress which reveal just how tiny your great aunt actually was. Even initials stitched roughly in red cotton onto bed-linen or underwear for laundering purposes in institutions have occasionally helped genealogists to identify their erstwhile owners.

One kind of needlework of obvious interest to family historians is embroidery or ‘fancywork’, a skill considered to be the highest form of sewing in the past and that practised most often by upper-class girls in the Victorian and Edwardian eras (and earlier). For an introduction to embroidery history see http://www.vam.ac.uk/content/articles/i/english-embroidery-introduction/. Any item from pillowcases to bookmarks could be embroidered. Beautifully decorated items such as hand towels, bed linen, handkerchiefs and table linen were commonly given as wedding, engagement or christening presents and may have been passed down through your family.

Embroidered designs may have many meanings pertinent to your own genealogy from a family coat of arms to symbols of Catholicism or other faiths, from the motifs of particular associations to national or regional emblems. Monogrammed items were very popular among the upper classes in the nineteenth century. Often the initials are very ornate and interlock or intertwine. You may be able to tell from a monogrammed item whether it belonged to a female, male or a married couple.

Female monograms tended to have the first initial of the woman’s name on the left, her middle initial on the right and her surname’s initial at a larger size in between. Male monograms tended to have all three initials in the right order and of the same size. If you were married and had your linen monogrammed then the husband’s first initial usually appeared on the right, the wife’s on the left and the (larger) initial of their married surname in the centre. Occasionally a young girl may have stitched her own initials and left a space for the initials of her intended – a sign of a union that never happened. Some items may also include dates and place names alongside personal names or initials. A recently discovered pair of lace doilies with the embroidered initials ‘L.J.R.’ and ‘E.P.’ also have the words ‘Dover’ and ‘September 1901’ sewn into them probably indicating the date and place of an engagement (for more on monogram etiquette see

http://www.belovedlinens.net/monograms/white-monograms-1-3.html)

Ancestors Who Sewed For a Living

Thousands of our working and lower middle-class ancestors (male and female) worked in the needle trades. Large numbers of such workers were required during the Napoleonic Wars (1805-1815) when they were employed to stitch sails and military uniforms. Women sewers were considered cheaper, more dextrous and less prone to ‘combination’ (i.e. early attempts at unionisation) than men. Soon their input was in demand in other sectors. Their experiences later in the nineteenth century have become the stuff of legend; many working for roguish employers in large sweatshops where pay and conditions were poor and the subject of much humanitarian concern.

Other poor women plied their needles at home. Sometimes, warehouses would distribute material to ‘mistresses’ or agents who would then apportion smaller amounts to individual home-workers. For women, needlework was an activity – like childminding, charring, washing, accommodating lodgers or selling food from their back kitchens – that could be fitted in and around other domestic duties. The home-based needle industry did not decrease as the nineteenth-century technological revolution progressed. Indeed some firms used more and more out-workers as factory and workshop regulations became more stringent.

Look out on censuses and certificates for a rich and varied terminology for the occupations of these needle-working ancestors, from the general (needlewoman, needle-worker, sewer, tailor, clothier, milliner, dressmaker, garment maker, seamstress or sempstress) to the specific and sometimes glamorous (gold embroideress, satin stitch embroideress, hosiery manufacturer, staymaker, garter-maker, mantua maker, shirt-maker, hat sewer, glover, boot and shoe stitcher, or bookbinder -who stitched and folded the pages of books). Related needle trades included button carding and hook-and-eye carding, umbrella covering, and sackwork. In the 1881 census nearly 5,000 women are accorded the occupation ‘sewing machinist.’

Censuses also pay tribute to the way in which different parts of the country specialised in different sorts of needlework. Ayrshire home-workers, for example, undertook ‘whitework’ – embroidery in white thread onto white cloth for christening robes, table cloths and underwear; Coventry made silk ribbons production; in Northampton, domestic stitchers assisted the boot and shoe industry. London had the largest women’s garment-making sector; and the South-West specialised in glove-making. You may find that all or nearly all members of your family worked at different aspects of the same trade. Whilst husbands and sons in Nottinghamshire, for example, made stockings in steam-powered factories, their wives and daughters sewed the seams at home.

If your ancestors worked as trained dressmakers in small shops or department stores, don’t be surprised to find them away from home on the night the censuses were taken. They may have served an apprenticeship in a city such as London or Birmingham before returning to a locality. The names of provincial and metropolitan dressmaking establishments can be found in local trade directories (many of which are now scanned and online at www.historicaldirectories.org).

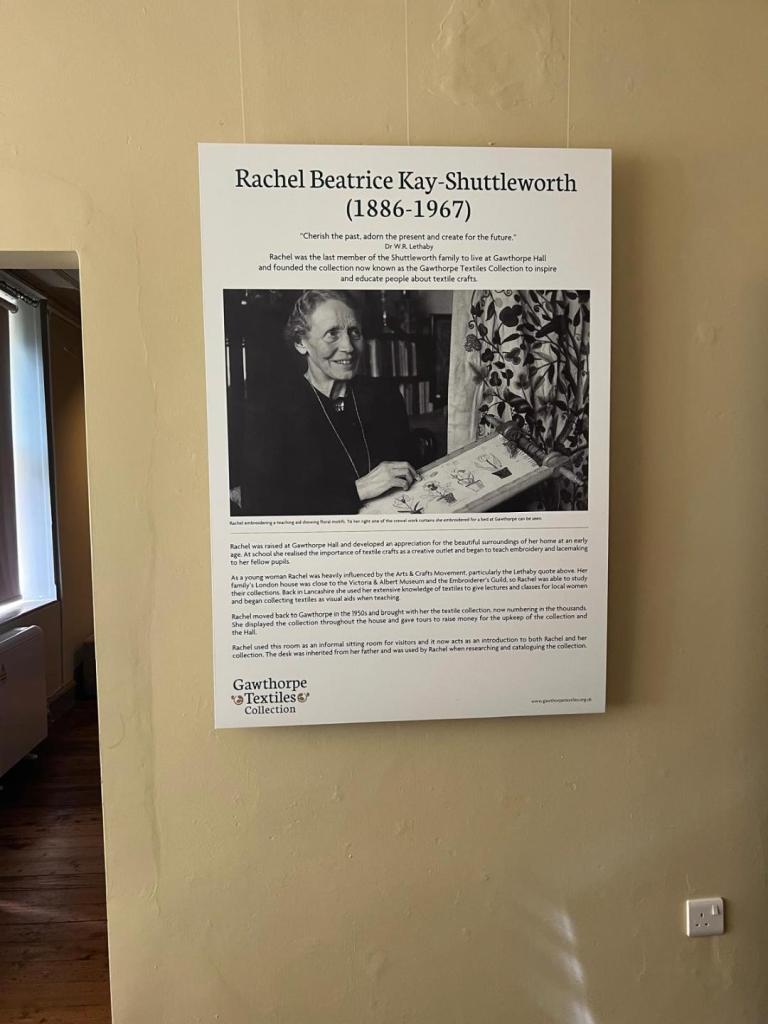

Personal Profile: Rachel Kay-Shuttleworth (1886-1967)

Rachel Kay-Shuttleworth was the daughter of (Baron) Ughtred Shuttleworth, Liberal MP, and granddaughter of James Kaye-Shuttleworth the educational pioneer.

Information panel at Gawthorpe Hall, Author’s own collection.

A keen needlecraft practitioner (with a particular talent for embroidery and lace-making), Rachel was heavily influenced by the anti-industrial ideas of the Arts and Crafts Movement. At the age of nine, she started to collect hand-decorated textiles from embroidered domestic items, to small items of costume, quilts and worked lace. By the time she was 26 she had amassed more than a thousand items the details of which (including date of acquisition, country of origin, date, donor’s name and a brief description of the item) she carefully recorded in a catalogue.

During World War One, Rachel was Secretary to the Civic Arts Society. She was a keen advocate of girl guiding in the Commonwealth and helped to establish the craft of gilding in Lancashire. During World War II, Rachel managed the Shuttleworth Estates and worked for the Women’s Voluntary Service. She moved out of Gawthorpe Hall in 1945 to support her nephew who was severely injured during the War.

In 1952 Rachel returned to the Hall where she continued to make, collect and lecture on textile items from around the world, opening the Collection to visitors and students in the hope that it would provide practical inspiration. You can view the Gawthorpe Textiles Collection at Gawthorpe Hall, Burnely Road, Padiham, Burnley BB12 8UA (see also : visitburnley.com/discover/gawthorpe-hall and http://www.gawthorpetextiles.org).

Key Sources

The Textile Society lists many small museums around the country which focus on specific aspects of textile history. (www.textilesociety.org.uk/textile-links/museums.php). The Royal School of Needlework (www.royal-needlework.org.uk/),based at Hampton Court Palace, has an archive of over 30,000 images covering every period of British embroidery history.

In London Victoria and Albert Museum has a helpful section on dating clothes in the decades between 1840 and 1960 whilst The Fashion and Textile Museum, (www http://ftmlondon.org/) looks at fashion and textile design from the 1950s to the present day. The Gallery of Costume in Manchester (http://www.manchestergalleries.org/our-other-venues/platt-hall-gallery-of-costume) houses over 20,000 items of clothing worn by men, women and children in the past. There are also impressive museums of costume in Bath and Blandford, Dorset, The Beamish Museum in County Durham has an extensive collection of patchwork quilts and rag rugs.

Ancestors who were employed as needlewomen occasionally appear in the records of philanthropic societies. For example, records for The Society for the Relief of Distressed Needlewomen (est. 1847) (which aimed to introduce fairer wages into the slop trade) and those of the Liverpool Society for the Relief of Sick or Distressed Needlewomen 1858-1941 (including weekly visitors committee minutes, distribution and account books), are at the Merseyside Record Office. There are also occasional rare finds to be made in local record offices. The Dressmakers’ Wages Books (1956-1969) of Edward Bates Ltd Department Store, Chatham and Blake and Son Ladies’ Outfitters, Maidstone, are held at Kent History and Library Centre for instance (search for these more generally through the National Archives website http://www.nationalarchives.gov.uk).

Extra reading

Karen Bryant-Mole: Clothes – History from Objects, Wayland, 1994.

Rozsika Parker, The Subversive Stitch: Embroidery and the Making of the Feminine, London: The Women’s Press, 1984.

Christine Walkley, The Ghost in the looking Glass: The Victorian Sempstress, London: Peter Owen, 1981.

Duncan Bythell, The Sweated Trades: Outwork in Nineteenth-Century Britain, London: Batsford Academic, 1978.

Margaret Stewart and Leslie Hunter, The Needle is Threaded: The History of an Industry, Heinemann/Newman Neame, 1964

Fiona Macdonald, Everyday Clothes Through History, Gareth Stevens Publishing, 2006.

Jayne Shrimpton, Family Photographs and How to Date Them, Countryside Books, 2008.

Philip Steele, Clothes and Crafts in Victorian Times, Gareth Stevens Publishing, 2000.

Canon G. A Williams Rachel Kay-Shuttleworth – A Memoir 1886-1967, Titus Wilsona dn Son, 1980.

Some useful websites

http://www.embroideryarts.com/embroidered_monograms/victorian Victorian monogramming styles.

http://fleurdandeol.com/Trousseau.php On the embroidery that decorated the wedding trousseau.

http://www.venacavadesign.co.uk/ Historical sewing patterns

http://medieval.webcon.net.au/index.html Historical needlework resources (pre-16th century)

http://ewhworkshop.biz/blog/?page_id=5 On the history of the sewing machine.

www.historicaldirectories.org Searchable local trade directories.

For Social History and Women’s History Books https://www.naomisymes.com/

Leave a comment